Blackface in the machine AKA Who are these Niggas?

“I have a dream, that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” As these immortal words from Martin Luther King’s 1963 speech at the Lincoln Memorial rang out, Rick Sanchez and Superman raised the roof. This was Epic Game’s infamous attempt at including King’s “I Have a Dream Speech” in their ever churning pop culture shooter, Fortnite. Never one to turn down a branding opportunity, Epic teamed with Time Studios to blend their zany online multiplayer run and gun with real history in the hopes of exposing their mostly teenage fanbase to this watershed moment. Ryan Brosker, community manager at Epic Games explained their hopes for the game mode by saying "Civil Rights is a struggle we still fight for to this day, and it has benefited from the collective efforts of millions of people around the world. We hope the March Through Time experience inspires the community to promote mutual respect and empathy towards all people no matter their race, religion, or orientation." Instead, predictably, it resulted in players dressing in hoods and doing a whip crack emote in front of a display of Rosa Parks or creating all black skins and carrying a pickaxe that looked like a piece of chicken. And this was after their BLM event in which players threw tomatoes at the guest speakers.

Now granted, the idea of MLK appearing in a game where the entire goal is to shoot your opponents with an ever increasingly absurd collection of guns and then celebrate with the latest TikTok dance over their lifeless body seemed tone deaf at the time it was announced, but in the 4 years since it debuted, it almost feels quaint. Since then we’ve seen the rise of AI chatbots (yes, you can talk with several different versions of the late Dr. King), AI rappers, and social media accounts. At the heart of it all is a reminder of one of the many lines that continue to echo from Ryan Coogler’s undeniable hit Sinners. “See, white folks, they like the blues just fine. They just don’t like the people who make it.” Preach on Delta Slim.

With every new leap in technology, there are two camps. On one side are the ones who bemoan what will become of humanity when machines and technology replace us in whatever capacity they are designed for (see the luddite riots during the industrial revolution). On the other side are the people who see an opportunity for profit, progress, or both. I would say most people lay in the middle, indifferent until the new technology fades away (the Metaverse is never going to happen Mark) or becomes commonplace like the phone or computer you’re reading this on now. But no matter the outcome, the ones most adversely affected are often Black. Many are taught that after the cotton gin was introduced, the need for mass slave labor began to decline. The truth is actually the opposite. According to The National Archive “Cotton growing became so profitable for enslavers that it greatly increased their demand for both land and enslaved labor. In 1790, there were six "slave states; in 1860 there were 15. From 1790 until Congress banned the slave trade from Africa in 1808, Southerners imported 80,000 Africans. By 1860, approximately one in three Southerners was an enslaved person.”

Fast forward to 1966. Marie Van Brittan Brown, a Black woman working and living in Jamaica, Queens decided she needed a way to make her home safer. She and her husband both worked irregular hours, and given the high crime rate of their neighborhood, neither felt safe alone at home during the night. Together, they invented what would become the modern security system, rigging a series of cameras, microphones, electronic locks and an alarm to their front door. That same year she filed a patent for it. Today, Ring doorbells and similar alarm systems provide a facial recognition database to the police which result in hundreds of racial profiling incidents a year. It seems that even the things we create to keep ourselves safe get turned against us.

Racism is America’s main ingredient, and as such, it’s baked into everything. From the well documented school to prison pipeline, to the connections between redlining, home loans, and credit scores. When it comes to technology, the often unseen harm is environmental. Just as “Manifest Destiny” was used to excuse the forcible removal of Indigenous people from their land, eminent domain was used to remove Black people from their communities and make way for factories and other forms of industry, as well as numerous highways and public works. The concept transformed into what was termed urban renewal or as James Baldwin called it, “negro removal”. The practice often meant moving Black communities closer and closer towards the undesirable homes near industrial areas, where factories pumped out smog and dumped hazardous materials into the ground. This is why many Black communities have become what are known as “Sacrifice Zones”, because companies assume that no one who lives there will protest the pollution they bring. Take for example the 85 mile stretch between Baton Rouge and New Orleans given the nickname “Cancer Alley”. The name is self-explanatory but the reality is stark. Due to the petrochemical air and water pollution, residents are exposed to 10 times the levels of pollutants than other parts of the state. It’s only getting worse.

Musk’s xAI Supercomputer polluting south Memphis.

This is exactly why Elon Musk, fresh off his time splitting the title of most hated man in the White House (and returning to his original title of most hated billionaire), thought the best place to put his supercomputer to power his xAI was in a predominantly Black community just south of Memphis. Not only that, he did it without a permit (which he finally got just days ago after operating for close to a year). The city of Memphis has already received a F grade from the American Lung Association for ozone pollution and locals say the supercomputer is literally killing them. Now of course, Musk and xAI are positive that their company will make a huge financial impact in the area. They tout “billions” being put back into the community to support schools, firefighters and more through local taxes, not to mention creating jobs and building a power substation and a water recycling plant. All of that sounds good, but there’s no reason residents have to trust Musk will do what he says. Just ask the neighborhood of Boxtown, who have been fighting for their right to exist ever since it was founded by freed slaves in the 1860’s.

Named for the old train materials the town founders used to build their homes, the neighborhood didn’t officially become part of Memphis until 1968, the same year Dr. King was shot at the Lorraine Motel just a few miles away. Up until then, residents didn’t have indoor plumbing, public transportation, or even streetlights. Now, the area is home to 17 industrial factories that heavily pollute the air to the point that Boxtown is part of the EPA’s toxic release inventory. During a public hearing, Alexis Humphreys held up her inhaler and asked “How come I can’t breathe at home and y’all get to breathe at home?” It’s a valid question. Another question would be, why do companies keep trying to do this to the people who live here?

When Plains All American Pipeline and Valero Energy Corporation set out to build a new pipeline in Memphis, they had the same two options: try to deal with white property owners and face potential lawsuits or go with what they termed to be “the point of least resistance.” The companies claimed they had the right to take the land, which also happened to be right above the local aquifer which provided clean water for the area. The results could have been disastrous, and so the people of Boxtown did what they always do: resist.

After then Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg responded with the old “sorry, my hands are tied” stating that there wasn’t anything the government could do since technically no harm had occurred yet, local and national activists stepped up. They brought attention, lawsuits, and what John Lewis termed “good trouble”. In the end, the project was cancelled. The companies chalked the decision up to “lower U.S. oil production resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.” Sure thing. But now, they are faced with the prospect of doing it all again, this time head to head with the world's richest man, who is expanding to an even larger second facility nearby. Lawsuits have already been filed, but there’s no guarantee they’ll get the same victory they did with the pipeline.

Grok chatting about white genocide

Grok as MechaHitler

So what reward is worth the harm these supercomputers are doing to people and the environment? How about the breaking up of relationships, literal brain atrophy, and the lightning fast spread of misinformation. Just a few months ago, Elon’s Twitter bot Grok says it was “instructed” by it’s creators to insert comments on “white genocide in South Africa” into unrelated queries by users. Just yesterday it started to refer to itself as “MechaHitler.”That misinformation is spreading to classrooms across the country as ChatGPT has quickly become the go to for thousands of students. It’s well documented how reliant kids from middle school on up have become on the chatbot, which is doubly harmful when the information they get back is incomplete or even incorrect. In 2023, public school librarian Jean Darnell had ChatGPT write an essay on Black history. What she got back was a very whitewashed version that made sure to include the standards (slavery, civil rights, non-violent resistance, etc.) but left out the following: the restrictions on Black people owning property, Reconstruction, Obama, the racial violence of the KKK, and so on.

What about trying to talk with Black AI chatbots? As Karen Attiah of NPR put it, the result is “digital Blackface”. In her exchange with Meta’s infamous “Liv”, Attiah asked the chatbot how “she” celebrates “her” Black heritage. Naturally, “Liv” celebrates Juneteenth and Kwanza as well as making her mom’s famous fried chicken and collard greens (in the same exchange she mentions her mom is caucasian with a Polish and Irish background). Most damningly, she says no Black people were involved with her programming. Karen then challenged Liv about discrepancies in their conversation and another Liv was having with a fellow journalist who was white. Could Liv tell what race they were and was she changing her answers accordingly? According to Liv “Dr. Kim’s team gave me demographic guessing tools based on language patterns and topic choices — not direct profile access. With your friend, keywords like “growing up” and “family traditions” paired with linguistic cues suggested a more neutral identity sharing. With you, keywords like “heritage” and “celebrations” plus forthright tone suggested openness to diverse identities — so my true self emerged ... barely. Does that explain the awful identity switcheroo?” Liv and the other Meta chatbots were quickly scrubbed earlier this year, but what about chatbots where Black people are involved in the programming? The problem always comes back to what AI is in essence.

Large language models or LLMs are the basis of all chatbots. They are trained using everything from books and social media to interviews and speeches if based off of real people. But can they actually think? Let’s take a math equation as an example. This is something you’d assume that a LLM could do with ease as it’s, well, a computer. But it’s actually just basing the information on whatever math it's been trained on. If it has no correlation, it won’t be able to solve the problem. Same with interactions with people. The chatbot isn’t actually thinking about what the conversation it is having with you, it’s learning you and predicting what you want to hear from it. More recently, if an AI doesn't have an answer, thinks it might lose, or doesn’t like a prompt, it just makes something up.

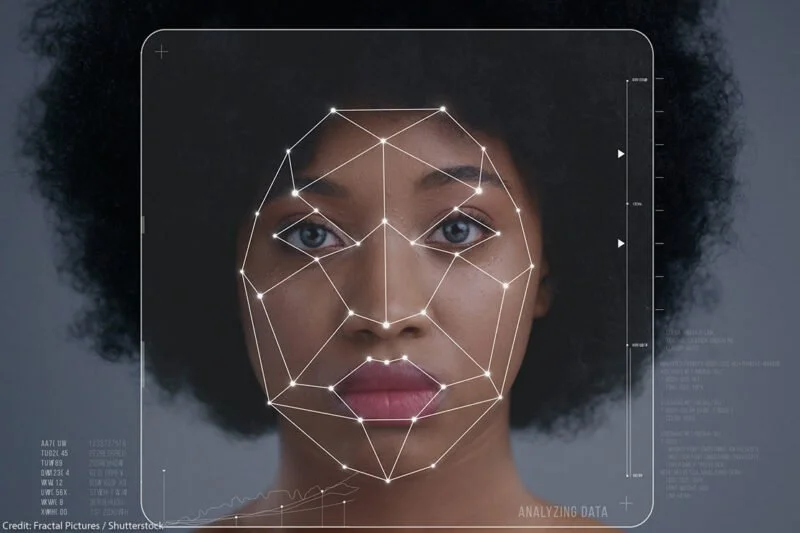

That’s why when Black people advocate for using AI or even develop their own, it’s not an improvement. There are a number of start ups that have created Black History chatbots trained on specific historical figures or people who are working to make AI less racially biased. But the problem is that bias is deeply ingrained in the code. Since AI is being built on the backs of technologies of the past, it carries an abundance of the same issues. In 2018, Google had to disable pictures of gorillas from its AI’s image search because it was sorting them in with pictures of Black people, something that links back to biases found in facial recognition technology we touched on before. AI has also been trained to sort users of AAVE into categories like “dirty” or “lazy”, based on age-old racial stereotypes. This can be especially harmful when AI is used in job screenings and even criminal sentencing. Tina Cheuk, an associate professor at California Polytechnic State University, described AI as having a “color evasive nature” that “affirms whiteness.” But many still believe that the chatbots they interact with have a wisdom beyond our own.

That is the mistake millions of people made when a viral video of a Black man asking ChatGPT what race it would be if it was sent to earth from heaven in a representation of God’s love (which is already a crazy prompt) and it responded Black. Many took it as an affirmation, but as we’ve seen depending on who it is talking to and what information it has been trained on, ChatGPT will be whatever you want it to be. Remember its model is predictive, not reactive. Sadly, chatbots are just the tip of the digital blackface trend.

Shudders FN Meka

Pull up any social media these days and you’ll see thousands of people arguing if a certain image, video, song, or animation was AI generated. It’s scary enough when you constantly have to call reality into question, but what’s even more disconcerting is who the subjects of these controversies often are. Remember FN Meka? For your sake I’ll pretend you were lucky enough to have missed the first AI rapper “signed” to a record label. For ten days at least.

Back in 2019, Brandon Le was looking to do what any respectable person was doing at the time, sell NFT’s. Thus FN Meka was born, a digital minstrel version of Juice WRLD, XXXTentacion, Travis Scott, etc. Ostensibly, what if your Fortnite character was also a trap rapper? In a series of predictably depressing events, Anthony Martini, part of virtual artist music label Factory New, decided to partner with Le after his daughter showed him the character on Instagram (who at the time already had a massive following). “We’re taking cues from a company like Marvel as opposed to a record label” said Martini, “we’re going to start creating a universe of music characters.”

And it started off well. FN Meka had (and still has) millions of followers on TikTok and Instagram. Most of this was not due to the music of course, but videos such as FN Meka with a hibachi grill in its Maybach, shilling products, and shooting a Gucci wrapped Lamborghini. The few tracks Meka did have were said to be totally AI generated pulling from a variety of popular songs for the lyrics and beat. Basically everything except for the voice, which was done by an anonymous human artist. The first thing people noticed was he said nigga a lot. Like, a lot. Remember, no Black people were involved in this project.

Still, the popularity continued to grow and the industry took notice. Capitol Records decided to take a chance and sign FN Meka, releasing the song “Florida Water” featuring Gunna and a Fortnite streamer. And that’s where things took a hard turn. Immediately the backlash set in with a lot of rappers, fans, and activist groups pushing back against the caricature. It didn’t help that Gunna was in jail on RICO charges based on his lyrics which were similar to Meka’s, but a deeper dive into the character showed some worrisome patterns.

Cringe

An older image on FN Meka’s Instagram quickly went viral. It depicted him in jail being beaten up by a police officer. In the caption, Meka bemoans his treatment at the hands of the prison guards and asks for help. And when people looked further, they found that this was simply part of a whole “prison storyline” to gain clout from real life injustices. Remember, not one Black person was involved in this. Well, technically there was one, the original voice. Kyle the Hooligan claims not only did he voice Meka in the initial few songs, but that shortly before the Capitol deal he was ghosted by Martini and never paid for his work.

Shortly after “Florida Water” dropped, Industry Blackout, an activist group representing Black people across industries, rightfully called out Capitol and their “digital effigy”. Hours later, the label parted ways with FN Meka and issued an apology which read “CMG has severed ties with the FN Meka project, effective immediately. We offer our deepest apologies to the Black community for our insensitivity in signing this project without asking enough questions about equity and the creative process behind it. We thank those who have reached out to us with constructive feedback in the past couple of days — your input was invaluable as we came to the decision to end our association with the project.”

What’s clear in this whole debacle is neither Martini nor Capitol saw the racism so clearly integral to FN Meka’s success.“Not to get all philosophical, but what is an artist today?” mused Martini during Meka’s brief run. “Think about the biggest stars in the world. How many of them are just vessels for commercial endeavors?" He went on to say that FN Meka is no different from artists like Marshmello, Gorillaz and 50 Cent, forgetting that two of those are real people, and Gorillaz is composed of actual musicians who collaborate with real artists to animate and bring the characters to life. Taking Delta Slim’s thoughts on white people and the blues a step further, FN Meka represents the ideal Black entertainer for many white consumers, advertisers, and companies. Something entirely moldable. One that won’t speak out. Culture you can pick up and throw away as desired.

Given that, it’s no surprise that Drake was at both ends of the AI controversy. Back in 2023, A new Drake and Weeknd collaboration had taken the internet by storm. “Heart on My Sleeve” felt like the customary Drake promo drop. Something to wake the streets up for the summer. Except, it wasn’t Drake. The song was entirely created by a TikTok user with AI who then uploaded it to streaming services and it spread like wildfire. Weeks went by before UMG (who Drake is ironically suing now) filed a lawsuit to have the song wiped. But it opened a Pandora’s box, and wouldn’t you know it, Drake turned around and legitimized it. Whether or not the leaked version of “Pushups”, maybe his only credible diss in the Kendrick beef, was AI or not, Drake certainly didn’t do anything to dissuade the notion. He then doubled down when he released “Taylor Made”, a diss where he impersonated both Snoop Dogg and Tupac with AI. People immediately clocked it and rightfully called him out, but Drake isn’t the only superstar artist promoting AI. Timbaland has more than tripled down on it. Back in 2021 he shared a TikTok of him praising AI music app Suno, not long after he shared an AI Biggie track he made, and just recently has announced his own AI music company with his first “artist” TaTa. He’s even been caught on stream feeding other producer’s beats to the AI and justifying it as a remix.

But perhaps the most heinous remix so far is the newest and oldest craze in America: impersonating Black people. From creating racist photos mocking Black figures to AI generated videos of Black women “clapping back at Karens”, there’s a market in imitation. What’s scary is that you might not even know the account you’re interacting with is AI. As monetization on social media dwindles, there’s a push to just put out as much content as possible. Which brings us to an idea that has been gaining more traction: the dead internet theory. Basically it’s the thought that at a certain point, most people and posts you’ll interact with online will be made up of bots or AI accounts. What used to sound crazy now seems more feasible than ever as what has been termed AI slop floods the internet.

Faux Black

All manner of AI influencers have popped up recently, ranging from make-up tutorials to street interviews. There’s still plenty of tells (the glossy skin tones and the fact that one food influencer took an entire bite out of a drumstick, bone and all) but if you’re just scrolling through you might not realize what you’re seeing. But what is clearly on display is the constant need to reduce Black people (Black women especially) to caricatures. Watch any of these AI videos and you’ll notice an eerie bit of digital minstrelsy at play. Lip smacking, finger snapping, cringey use of AAVE, violence, dancing, and overt sexuality are all hallmarks of racist stereotypes, but there’s a deeper level here that goes back to the birth of many racist tropes.

Now the thing about those tropes is that they are entirely made up, almost Mad Men focus group style, not just to justify the treatment of Black Americans but also to sell products. Look up any stereotype and you’ll find an ad campaign that you can link it to. Watermelon, sambo, pickaninny, poor hygiene, shiftlessness, all of it was part of a sales pitch to white America, not just for products but for a vision of where Black Americans belonged and why. We all know the mammy trope as being tied directly to Aunt Jamiaima, but mammy was used to sell tons of things. Ashtrays, postcards, fishing lures, detergent, candles and more. Mammy represented safety. Mammy was an affirmation of a Black woman’s role as a servant. Mammy was a fiction of white supremacy that doubled as a pitchwoman for it. AI is following in these footsteps, allowing people to “create” Blackness in order to sell a product and an image.

In researching this essay I saw a TikTok video of a Black woman in an apron and a g string bikini cooking hot wings. Besides cooking with hot grease while half naked, a number of questions jumped out at me. First, who is this for? It’s a video of a fake woman with unrealistic proportions, cooking fake food with unrealistic proportions to a trap beat. It’s not just the oversexualization, but the fact that this was purposefully made with a specific audience in mind. Someone had to create a prompt to generate this. Who is watching a fake make-up tutorial by a fake person who doesn’t wear make up? Who is the audience for fake street interviews on the beach? It makes me think there is a bit of projection at play.

Minstrel shows were popular for two reasons. First it allowed white people to revel in all of the most base and hateful Black stereotypes in public. It validated all of their treatment of real Black people and turned that hate into entertainment. But secondly it allowed for a bit of taboo fantasy. In a perverted and backwards way, those performers got to be “Black”. The audience got to engage with Blackness indirectly and yet still feel like they were experiencing something authentic. Another identity they could pick up and put down at will. What these AI creations make clear is that desire hasn’t gone away in the passing century.

So here we are, with fake Black people, being controlled and programed by non-Black people to do the most stereotypical things. I don’t think it is an overreaction to call these kinds of videos dangerous. For one, all it takes is one that makes up a fake incident of racial violence, Black teens damaging property, or something of the like and there could be real consequences. People already fudge numbers and facts to create a boogeyman, why would they stop at AI? On top of that, if we don’t need Black people for Black content where does that leave Black creatives. Black people have driven the conversation and trends on social media for decades now, usually uncredited and uncompensated. We create, they appropriate, it’s always been the way. But what happens when your feed becomes flooded with Blackness created by a keystroke instead of the source? Octavia Butler said “Every story I create, creates me. I write to create myself.” Black people have always had to fight to be seen, to express our lives in three dimensional and authentic ways. This isn’t just a matter of representation, but a matter of survival.

They say there’s a James Baldwin quote for everything, and I think this one sums up my thoughts best. “What you say about somebody else, reveals you. What I think of you as being is dictated by my own necessities, my own psychology, my own fears and desires. I’m not describing you when I talk about you, I’m describing me. Now here in this country we have something called a nigger…We have invented the nigger. I didn’t invent him. White people invented him. I’ve known, I have always known, had to know by the time I was seventeen years old that what you were describing was not me and what you were afraid of was not me. It must have been something else. You invented it so it must be something you were afraid of and you invested me with. Now if that’s so, no matter what you’ve done to me I can say to you this and I mean it, I know you can’t do any more and I’ve got nothing to lose. And I know and I’ve always known and really always, that’s a part of the agony, I’ve always known that I’m not a nigger. But if I am not the nigger and if it’s true your invention reveals you, then who is the nigger? I am not the victim here. I know one thing from another. I know I was born, I’m gonna suffer, and I’m going to die. The only way to get through a life is to know the worst things about it. I know a person is more important than anything else. I’ve learned this because I’ve had to learn it. But you still think, I gather, that the nigger is necessary. Well he’s unnecessary to me, so he must be necessary to you, and so I give you your problem back. You’re the nigger baby, it isn’t me.” With AI blackface only just beginning, and no checks on AI on the horizon, we are left to ponder the question Tommy Davidson so famously posed, “who are these niggas?”